We don't need more money for mental health

You regularly hear politicians talking about how the NHS needs more money for mental health. In today's post, I want to challenge this idea and offer a very different explanation and very different solution.

First, some caveats. This post is about British politics. This blog typically talks about managing your mental health, so I want to make it clear from the start that this post is not in a similar vein. You may find it interesting anyway, of course.

Now, on with the article:

The mental health epidemic

You may have heard the claim that we are currently experiencing a mental health pandemic.

The World Health Organization has championed this idea1, noting that:

- Over 300 million people suffer from depression

- It is the leading cause of disability worldwide

The evidence on the wall is quite compelling.

The Lancet notes that 30% of people will suffer from anxiety at some point in their life2.

Some of this could be due to better rates of diagnosis. However, multiple studies have shown that this does not account for most of it: we genuinely see far higher levels of anxiety and depression in the modern era3.

So yes, we are living through a mental health epidemic. Rates of anxiety and depression have never been higher, despite the fact that we are living in a world that is safer and more comfortable than it has ever been.

Services are being stretched

Given the rise of anxiety in recent decades, it would be entirely understandable that mental health services in the NHS have been stretched by the sheer volume of people who now need their help.

To say this challenge has gone unmet, however, would be unfair.

Over the past 12 years, the NHS has developed IAPT, short for Improving Access to Psychological Therapies. These initiatives now handle the bulk of the workload: if your doctor refers you for common health problems such as anxiety and depression, they will typically send you to the local IAPT.

This has been a huge success, particularly in recent years.

At Anxiety Leeds, it used to be common for people to talk about being on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) waiting list for a year or two. Today, Leeds IAPT get most people into treatment within 12 weeks, according to their reports. Anecdotal evidence from our group seems to support this claim.

The myth of under-funding

The support provided by the NHS is not without criticism, however. Many people feel frustrated that the only options on the table are often CBT or medication.

For the most part, this is true. Other therapies, and particularly the talking therapies, are difficult to access or simply unavailable entirely. Those who want to pursue these options must often find the money to do it privately.

So, is it the case that the NHS simply doesn't spend enough money on providing a range of treatments, due to lack of funding for mental health?

Hardly. In fact, the NHS spends an enormous amount on it.

How much do they spend?

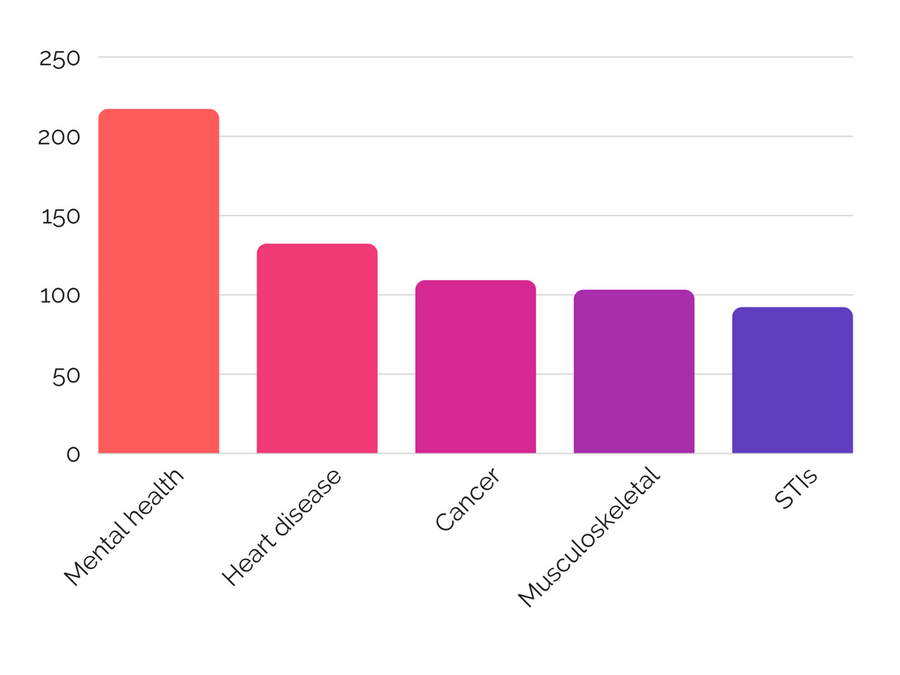

More than anything else on their balance sheet4. Mental health is number one. We are talking bigger than cancer. And bigger than heart disease. In fact, it's so big, that they spend as much on mental health as cancer and heart disease put together. Anything else is a distant fourth.

This is notable. Cancer and heart disease are the biggest killers in the UK.

Mental health, on the other hand, does not kill that many people. Sure, it robs us of quality-of-life years. Those of us who struggle with anxiety will know how painful it can be.

But, to have some objectivity, it has to be said that most of us go on living regardless. Someone who needs surgery or chemotherapy has a much higher mortality rate. They are imminently going to die unless they get treatment.

Nor is it a numbers games. Common mental health issues affect one in three people. But cancer does, too.

So, mental health does not get a bum deal when it comes to NHS spending. It is a top priority for them.

Where does the money go?

Let's be clear about where the money is being spent.

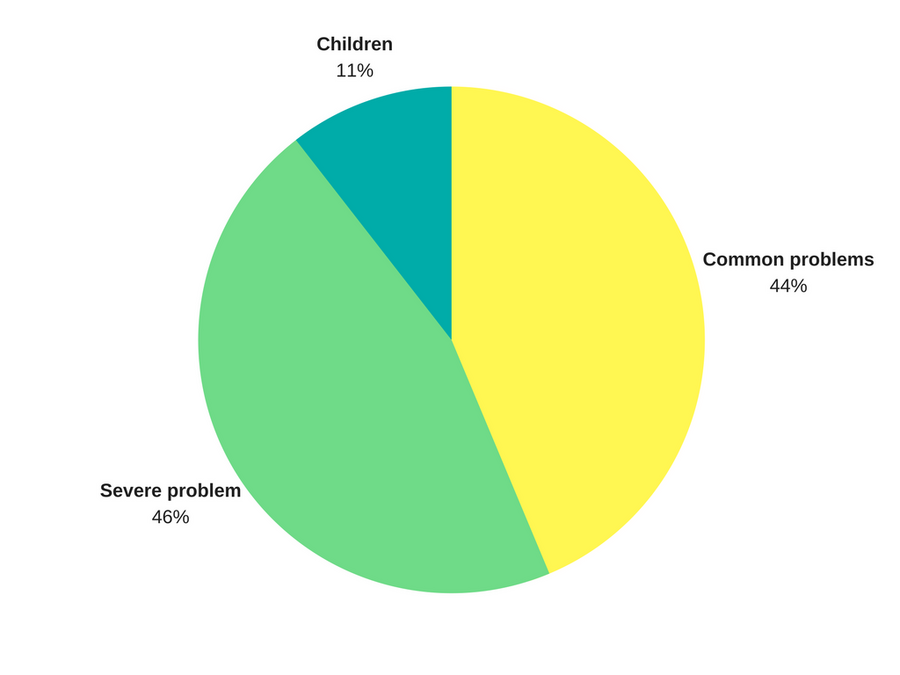

Mental health contains a huge range of issues. So, you might think the money is going elsewhere: on inpatient treatment for more serious disorders, for example.

This kind of care is not cheap. It costs the NHS £300,000 a year to keep someone in Broadmoor5.

Severe mental illness is a bigger burden on healthcare spending than common mental health issues. However, it's not much. Total spending on each area accounts for £8.7 billion for severe compared to £8.3 billion for common6. So, even when we narrow down spending to common issues like anxiety and depression, the money is there.

Would more money help?

Yes and no. Mostly no, though.

As we have already seen, there is a lot of money going into mental health. The problem is that the solutions we have are not cost effective.

It is expensive to train up a therapist and put them in a one-on-one situation with someone, every week, for an hour, for three to six months. This is not a one-time process: many people require several rounds of therapy. Plus any medication to go along with it.

More funding would allow us to train up more therapists, and possibly offer a wider range of therapies. However, CBT is used primarily because it works better than anything else. So, increasing the range of therapies would lead us to diminishing returns. And training more therapists is prohibitively expensive because of the limited patient load one therapist can take.

It is not more money we need: it is more effective treatments.

This, if we were to increase spending on mental health, is where we could spend it. However, for the most part, it is unnecessary. We already know some of the most significant aggravating factors for poor mental health.

What is the real cause of the epidemic?

Let's take a step back and consider why the rates of mental health issues are spiking. If we can solve that, and reduce the issues in the first place, the entire debate about funding becomes irrelevant.

The international picture is unclear. It does not appear to be connected to the standard of living. Many Western countries struggle with high rates of prevalence, with the United States taking the top spot7. However, many Eastern countries see high rates of prevalence, too, including India, China and Brazil8. On a global scale, it is difficult to discern any pattern.

WHO estimates clearly show an increase in mental health problems, though9.

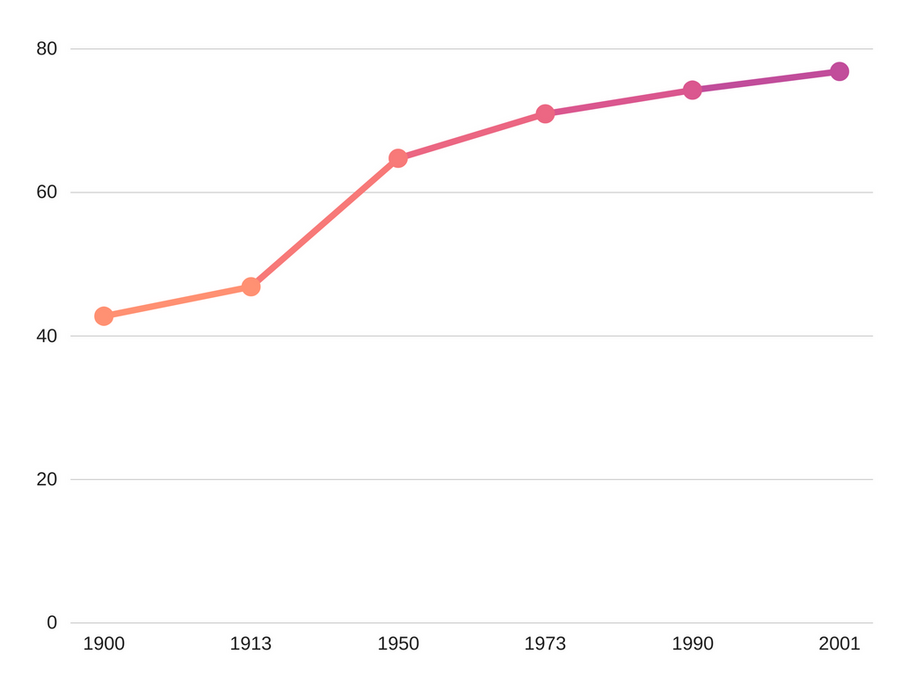

One reason for this could be that people are living longer. While these problems can affect you at any age, depression in particular spikes between 30-40 and 50-60.

But the nature of society itself is changing, too. Gone are the close-knit communities, simple diets and strenuous lives of our ancestors.

Why modern life is hard

I love progress. Every year the world gets safer and less violent. Fewer people live in poverty. Life expectancy increases and infant mortality decreases. It's all brilliant.

But progress is a double-edged sword.

Take diet, for example. We can now have a diet that is more varied than ever. Every food is always in season thanks to a worldwide distribution network and supermarkets open 24 hours a day. But we can also choose to eat nothing but sugar.

We are no longer forced to do backbreaking labour on our household farms. But now we can choose not to exercise at all.

We are no longer forced to live on the goodwill and support of our neighbours. But can now coast through life without having a meaningful relationship with anyone.

Today we have to choose to exercise, and eat right, and build relationships. Or, we can choose not to. Any many of us do.

In 1962, just 13% of adults in the United States were obese10. Now it is 36%. Less than a third of people are friendly with their neighbours, and for young people, the figure is as low as 18%11.

This is a problem because we know that these areas are critical to maintaining good mental health12.

The modern world allows us to make social and lifestyle choices that are terrible for our mental health. And we do because we're only human and we the short term rewards are generous: we feel great when we avoid a social anxiety provoking situation or eat a chocolate bar, for example.

What is the solution?

We need to look at how we can bake healthy living into society.

This can be done in a way that will not impact people's freedom of choice. In Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness13, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein set out the idea of libertarian paternalism.

This is the idea that we use sensible defaults and encouragement to steer people in the right direction, without forcing their hand.

Take pensions, for example. You can give people a choice whether they want to save for their retirement while opting them in by default. This means that if someone wants to opt out, they can. But most people are happy to stick with the default and therefore make sensible choices for the long term.

If we could employ similar strategies to make it easier for people to make healthy choices in areas such as relationships, exercise, diet and sleep, we would see a big improvement in people's health.

This strategy is not easy

It's easy to say "everyone should be healthier", but more difficult to come up with a solution on how to implement this. We already have many government initiatives set up to try and achieve this. Just to name a few:

- Additional tax on sugary drinks and unhealthy food

- A partial ban on advertising junk food on TV

- Cycle to work schemes

- State subsidies of parks, sports teams, and leisure facilities

- Community centres

One could argue that not enough is being done, or that the current approaches are not working. Both of these are possibly true.

It could also be argued that we are targeting the wrong things. Relationships, rather than diet and exercise, is perhaps the most key component of maintaining good mental health. But how do you get people to build friendships with their neighbours in a world where we are all scared of each other?

I don't know. But, if I had a big pot of money to invest in improving people's mental health, spending some of it to try and find out seems like an excellent idea to me.

Conclusion

Few would deny that the modern world is a vast improvement over that of 50 or 100 years ago. Those who would, have simply not looked at the facts.

However, the rapid change in society has brought with it fresh challenges, and one of the most potent is the dramatic rise in anxiety, depression and other mental health issues.

To fix this, we could continue to pour even more funding into existing methods. However, they already receive a substantial pot of money. Given the current efficacy rates and diminishing returns, this will not provide a long term solution.

A better approach would be to look at society itself. Today, it is too easy to make choices that negatively impact our mental health, whether it is relationships, exercise, diet or sleep.

Fixing these problems is not easy, and would not eliminate mental health issues. But it would reduce them to a level where we can give those still struggling with the in-depth help and support they need.

Metadata

Published 14 August 2017. Written by Chris Worfolk.

References

-

Depression fact sheet. World Health Organization. February 2017. Link. ↩︎

-

Prof Michelle G Craske, Prof Murray B Stein. Anxiety. The Lancet. 24 June 2016. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30381-6 ↩︎

-

Jean M Twenge. Are Mental Health Issues On the Rise? Psychology Today. 12 October 2015. Link ↩︎

-

Nuffield Trust. Categories of NHS spending per head. 14 November 2014. Link. ↩︎

-

Sharon Sutton. Broadmoor - Inside Britain's Highest Security Psychiatric Hospital. Huffington Post. 10 March 2017. Link. ↩︎

-

Mental Health Taskforce reporting to NHS England. Te five year forward view for mental health. February 2016. Link. ↩︎

-

Allison Van Dusen. How Depressed Is Your Country? Forbes. 16 February 2007. Link. ↩︎

-

Wikipedia. Epidemiology of depression. 17 July 2016. Link. ↩︎

-

World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. 2017. Link. ↩︎

-

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Overweight & Obesity Statistics. October 2012. Link. ↩︎

-

Alex Delmar-Morgan. Love thy neighbour? Most British people don't even know what their names are. The Independent. 13 October 2013. Link. ↩︎

-

Chris Worfolk. Do More, Worry Less: Small Steps To Reduce Your Anxiety. 2 May 2017. ISBN: 1544025572. ↩︎

-

Richard Thaler, Cass Sunstein. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. 8 April 2008. ISBN: 978-0-14-311526-7. ↩︎